Richard Hollerman

We know that “drinking” is a rather generic term that indicates that the person in question is “drinking” and not “eating” or anything else. But when we think of “drinking,” of course, we generally are thinking of drinking alcoholic beverages.

In the 1700s and 1800s we know that America, especially rural America, was known for Ale and Beer. We also think of Cider, as a drinking beverage, was popular. There was also Rum. People drank much in those days, with much beer and the like consumed. In fact, in many ways there was much drunkenness in those days too. Even children would drink at home and at school. And some of it had to do with the fact that water was considered contaminated or undrinkable, thus the alcohol would kill the bacteria and make the contents drinkable.

Alcohol was consumed in the early days of America, with numerous means of inebriation during the 1800s. Prohibition was something known by this term, beginning in the 19th century. By “prohibition,” we are aware that alcoholic beverages were “prohibited” to be drunk. We find this opposition to drinking in the 1800s and until 1919 when opposition to alcohol became the litmus test of orthodoxy. We find a strong emphasis, led by Methodists, Presbyterians, and other denominationalists to outlaw all alcoholic beverages (such as beer, wine, and other alcoholic intoxicants). (Technically, and legally, “prohibition” was from 1920 until 1933.)

This opposition was passed by 46 of the then 48 states and for many years, in the United States, this was the “law of the land,” although there were exceptions. Catholics opposed it. Even some Lutherans (who had come from Germany where beer was popular) opposed it. Evil people opposed it. Worldly people opposed it. (We know that there were very, very few Catholics at the beginning of the country, in 1776, but they became more and more increased as the years went by).

Thus, women, professing Christians, and others brought “prohibition” in. The government was involved, especially in the1800s through the1900s. We think that the issue of “germs” was of little consequence in the 1800s and 1900s.

We might ask why the abolition of prohibition in the United States in the latter 1920 until it was accepted in 1933. This is what one source says:

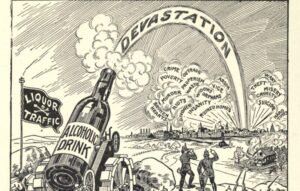

The increase of the illegal production and sale of liquor (known as “bootlegging”), the proliferation of speakeasies (illegal drinking spots) and the accompanying rise in gang violence and organized crime led to waning support for Prohibition by the end of the 1920s. (The History Channel.)

Thus, it seems that illegal sale of liquor, illegal drinking spots (especially in major cities, such as New York, Chicago, and the like), and gang violence led to the decrease of support for the prohibition of liquor.

We also find the following:

The roots of the temperance movement stretch all the way back to the early nineteenth century. The American Temperance Society, founded in 1826, encouraged voluntary abstinence from alcohol, and influenced many successor organizations, which advocated mandatory prohibition on the sale and import of alcoholic beverages. Many religious sects and denominations, and especially Methodists, became active in the temperance movement. Women were especially influential. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union, founded in 1873, was one of the leading advocates of prohibition. (Kahn Institute)

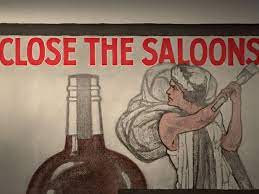

During the Progressive Era, calls for prohibition became more strident. In many ways, temperance activists were seeking to ameliorate the negative social effects of rapid industrialization. Saloons and the heavy drinking culture they fostered were associated with immigrants and members of the working class, and were seen as detrimental to the values of a Christian society. The Anti-Saloon League, with strong support from Protestants and other Christian denominations, spearheaded the drive for nationwide prohibition. In fact, the Anti-Saloon League was the most powerful political pressure group in US history—no other organization had ever managed to alter the nation’s Constitution. (Kahn Institute)

We also have this as background information regarding the eighteen amendment (outlawing beer, wine, “spirits,” ale, and so forth):

Led by pietistic Protestants, prohibitionists first attempted to end the trade in alcoholic drinks during the 19th century. They aimed to heal what they saw as an ill society beset by alcohol-related problems such as alcoholism, family violence, and saloon-based political corruption.

Many communities introduced alcohol bans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and enforcement of these new prohibition laws became a topic of debate. Prohibition supporters, called “drys”, presented it as a battle for public morals and health. The movement was taken up by progressives in the Prohibition, Democratic and Republican parties, and gained a national grassroots base through the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. After 1900, it was coordinated by the Anti-Saloon League.

Opposition from the beer industry mobilized “wet” supporters from the wealthy Roman Catholic and German Lutheran communities, but the influence of these groups receded from 1917 following the entry of the U.S. into the First World War against Germany.

Thus, we can see that there was a fierce battle between those who opposed manufacture and sale of intoxicants and those who promoted them. “Wet” (those who endorsed this sin) were aided by wealthy Roman Catholic and Lutheran communities. The depression era (about 1930 and later had a telling effect on support for outlawing this. The fact that rural America that generally opposed liquor was involved and the urban criminals promoted all of this had a telling effect.

Finally, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) of New York, became president of the United States, he abolished the Eighteen Amendment and the Twenty-first Amendment went into effect. Alcohol became legal in the country again. Worldly people, of course, rejoiced in this while many (especially the religious and conservative) lamented it. But this period (the so-called Prohibition days, named after the fact that intoxicants were forbidden) was both a bane and a blessing in many respects.

This was the period of organized power for the evil liquor industry. The gangs proliferated. It was the day of Al Capone, the criminal “boss” that promoted criminal activity (who was later captured). And all of this led to the defeat of a noble experiment. Increased poverty abounded. And, the women’s temperance emphasis waned. Crime increased. Increasingly, the era of Prohibition ended.

It was not gone completely, however. I recall that in school, each week half of the class (the Protestants, while the Catholics remained in class) went to weekly Bible classes and toward the end each year, we as a class were encouraged to sign a pledge to keep away from “intoxicating beverages” by the local temperance group. I well remember those days and that event.

Today, we rarely find mention made of the Prohibition era. Temperance is passé. Conservative causes have decreased. Morality seems to be a thing of the past. Catholics and other liberals have ascended or religious causes have nearly disappeared. People do want their liquor, drugs abound—and abstinence has decreased. Prohibition is nearly gone.

You can reach us via e-mail

at the following address:

You can reach us via e-mail

at the following address: