“Black Lives Matter” or “All Lives Matter”?

Lessons from America’s Past

Richard Hollerman

Not long ago we wrote and posted an article dealing with a common and relevant topic today—whether all lives matter. We know that there are some in America that emphasize that “black” lives matter and this is an important thing for us to decide. This has been in light of the widespread carnage, stealing, murder, and mayhem that we see on the streets of such cities as Chicago, Portland, Seattle, Philadelphia, and other large American cities.

I suppose that I am somewhat naïve but now I realize that BLM means “black lives matter.” Of course, this is true. God made blacks and He also made all shades of skin color, depending on the amount of melanin in the skin. But I doubt that we should emphasize the differences in skin color as we seek to view all things as God does.

We know that the labels that we attach to color and many other things serve to widen the gulf between people. As we read in Scripture, from the time of Abraham until the time of Christ, there was a God-sanctioned division of humanity and this was between the Jews and the Gentiles (or the non-Jews).

But this has been removed and now the only division is between those who believe in Christ and those who do not. In other words, God encourages us to see a difference between those who accept Him and those who don’t. All other secular and physical divisions have been removed—and this would include blacks and whites, as well as browns, yellows, and others.

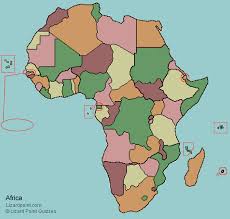

Blacks were known as “Negros” at one time in history. And then this ethnic group were called “colored” people—since they were not white. (We’ve heard some older people, including “blacks,” call non-whites “colored” too.) And then they were called “blacks” perhaps to emphasize that they were not white in color. This was in the past but today this is also in vogue. More recently, they have been called “African-Americans” (especially in academic circles) and we find this somewhat misleading. Yes, they did come from Africa in the beginning but now they are from America. Why not just call them “Americans”? But we generally do know them as “blacks” and we are content with this.

By 1750, we learn that there were about 200,000 blacks in America. “The majority lived in the South, where the warm climate and fertile soil encouraged the development of plantations that grew rice, tobacco, sugar cane, and later cotton” (The World Book, Vol 1, p.136d). We also learn, “Only 12 percent of slaveowners operated plantations that had 20 or more slaves” (Ibid.). We then read this: “By the early 1800s, more than 700,000 slaves lived in the South. They accounted for about a third of the region’s people.” (Ibid.) They were especially plentiful in South Carolina, Maryland, and Virginia. Then, by the time of the Civil War, there were perhaps four million slaves in the South. (Ibid, p. 136e).

This gives a bit of the background that will expand our knowledge. The blacks began to come to this country (of America) in the 1600s and this has continued until the present. By the time of the Civil War (1861 to 1865) there were some four million blacks (as we mentioned above). The “Emancipation Proclamation” of President Lincoln, which may be dated about 1863, freed the blacks. Today there are some 46.8 million blacks in America. This is according to Pew Research that tells us that there are about 14 percent of the American public who self-identify as blacks.

It may be good to realize that having this number of blacks in the country in the 1860-65 period posed a problem—a serious problem. This is something that Lincoln could see and many others could also see it beforehand. The “solution” that he and others proposed was that those who wanted to would be sent back to the country or countries of their origin. Perhaps we should call this the “continent” of their origin rather than the “country” of their origin since these people came from more than one country.

From what we can learn, they came from various African countries, such as the following:

80+ percent of all slaves arriving in North America came directly from Africa

- Senegambia—13 percent (coast between present day Senegal and Gambia)

- Gold Coast—16 percent (most of present day Ghana)

- Bight of Biafra—23 percent (most of present day Nigeria and Cameroon))

- Windward Coast—11 percent (present day Liberia and Ivory Coast)

- Region between Angola and Congo—25 percent (present day Congo, Zaire, Angola, Namibia)

These blacks were captured as parts of raids by other blacks in Africa, then they were sold to outsiders, including Portugeses, French, Spanish, English, and others. (https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/African_American_Place_of_Origin).

Many of these slaves of black extraction had either been made slaves by African Muslims or by their own pagan black Africans. (They were not captured by the slave shipmasters themselves.) Then they came West to the Americas—from the Spanish, Portuguese, French, English, and others. Sadly, they were pulled from their own country, loaded on ships in a most inhumane way, with the killing of many, and brought to the “new world” of America.

There they generally became “field” workers although many of them did work in other types of jobs—household workers, railroad workers, timber workers, etc. (And some were highly-skilled craftsmen.) As we have stated elsewhere, only about five (5) percent of the incoming slaves were brought to America and 95% were brought to other places in the Western Hemisphere (such as Brazil, Cuba, Haiti, and elsewhere).

The “American Colonization Society” in 1816 proposed a way that these slaves could be freed and allowed to return to the continent of their origin. This was proposed by John C. Calhoun of South Carolina and Henry Clay of Kentucky. In 1822, this society established a homeland on the west coast of Africa called “Liberia” (from liberty, obviously). This became the first “self-governing black republic in Africa” in 1847 (Ibid.). Interestingly, most blacks wanted to stay in America and considered this their home! Consequently, only about 12,000 slaves returned “home” whereas millions chose to stay in the United States of America.

Abraham Lincoln, the senator from Illinois and then the president of the United States, in 1860, proposed a way to “help” these emancipated slaves to return to the “continent” of their origin. He offered to give them a certain amount of money and send them back! However, as we mentioned above, most had adopted American ways and didn’t want to return. They were content here!

We find this explanation during these turbulent but climactic times: “In March 1862, Lincoln gave Congress a plan for the gradual freedom of slaves. The plan included payment for the slaveowners. In April, Lincoln approved legislation that ended slavery in the District of Columbia and provided funds for any freed slaves who wished to move to Haiti or Liberia. In June, Lincoln signed a bill that ended slavery in all federal territories.” (Ibid.)

The freedom of slaves might be mentioned: “The final order was issued on January 1, 1863, as the “Emancipation Proclamation.” African Americans referred to that day as the Day of Jubilee. Bells rang from the spires of most Northern black churches to celebrate that day” (Ibid). All was not well, however. Southern whites, for instance, thought that “whites were born superior to blacks with respect to intelligence, talents, and moral standards” (Ibid.).

It might be good to remind ourselves that only about five percent (5%) of the slaves were sent to North America (the United States). A high percentage went to Brazil, to Haiti, to Cuba, and to other countries in Central America, the Caribbean islands, and South America. We should always keep this in mind when we think of slavery. (Perhaps this is one reason why there are so many dark-skinned people in these nations.) Few did come to North America—and most went elsewhere. This is not to excuse the horrible conditions to which they went but it is a means of emphasizing where they did go. They were needed in these places to work with sugar cane, tobacco, cotton fields and in other types of jobs. .

I suppose that white Americans would think that this “solution” to the “black problem” might be the best one, but most American blacks did not want this. As we said above, only some 12,000 returned and the rest did not come. Lincoln was not the only one who wanted to offer blacks a way to return to their homeland.

Let’s see what secular sources say about this period in the history of the United States:

Starting 50 years before the end of slavery, the American Colonization Society moved 12,000 people from America to West Africa.

The biggest question facing the leaders of the United States in the early 19th century was what to do about slavery. Should it continue or should the U.S. abolish it? Could the country really be home to free Black people and enslaved black people at the same time? And if the U.S. ended slavery, would freed men and women remain in the country or go somewhere else?

Many white people at this time thought the answer to that last question was to help these free Black Americans go to Africa through “colonization.” Starting in 1816 or 1817, the American Colonization Society began in New York—which counted future presidents James Monroe and Andrew Jackson among its members—sought to create a colony in Africa for this purpose. This was 50 years before the U.S. would abolish slavery. Over the next three decades, the society secured land in West Africa and shipped people to the colony, which became the nation of Liberia in 1847.

The society spent its first few years trying to secure land in West Africa. In 1821, it made a deal with local West African leaders to establish a colony at Cape Mesurado. The strip of land was only 36 miles long and three miles wide (today, Liberia stretches over 38,250 square miles) The next year, the society began sending free people—often groups of families—to the colony. Over the next 40 years, upwards of 12,000 freeborn and formerly enslaved Black Americans immigrated to Liberia.

The American Colonization Society was distinct from Black-led “back to Africa” movements that argued Black Americans could only escape slavery and discrimination by establishing their own homeland, says Ousmane Power-Greene, a history professor at Clark University and author of Against Wind and Tide: The African American Struggle against the Colonization Movement. Though some free Black Americans may have supported the society’s mission, there were also plenty who criticized it.

“They argue that their sweat and blood, their family who were once enslaved, built this country; so therefore they had just as much right to be here and be citizens,” he says. In addition, many argued “this is a slaveholders’ scheme to rid the nation of free Blacks in an effort to make slavery more secure.”

In the beginning, the American Colonization Society didn’t uniformly believe that slavery should end. The society was made up of white men from the north and south, including slave owners who felt that free Black people undermined the institution of slavery, and should be sent away. Others in the society felt that slavery should be gradually dismantled, but that Black people could never live freely with white people.

As the abolitionist movement grew in the early 1830s, abolitionists’ criticism of the society began to erode its support. Unlike the white people in the American Colonization Society who believed that slavery should gradually end, abolitionists called for an immediate end to slavery. In addition, many abolitionists considered it cruel to deport Black Americans to Liberia, where they struggled to survive in a new environment with new diseases.

In 1854, future president Abraham Lincoln agreed with this sentiment when he gave a speech that mentioned colonization as an appealing solution to the moral evils of slavery—but noted its logistical and ethical challenges:

“If all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do, as to the existing institution. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia,–to their own native land. But a moment’s reflection would convince me, that whatever of high hope, (as I think there is) there may be in this, in the long run, its sudden execution is impossible. If they were all landed there in a day, they would all perish in the next ten days; and there are not surplus shipping and surplus money enough in the world to carry them there in many times ten days.”

President Joseph Jenkins Roberts had his official residence in Monrovia, Liberia in the 1870. Liberia became the first African colony to gain its independence.

In particular, the Black abolitionist Nathaniel Paul and the white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison helped discredit colonization by debating its proponents in public. In the early 1830s, Garrison published a book called Thoughts on Colonization containing “big passages of Black Americans saying why it’s bad,” Power-Greene says. Among people who already believed slavery should end at some point, “abolitionists convinced most people, particularly in the northeast, that the colonization movement is anti-Black.”

The American Colonization Society evolved throughout the 1830s so that by the end of the decade, it began to support immediate abolition while still promoting its colony in Africa as a place for free Black Americans to relocate. This caused the society to lose support among southern slave owners who were committed to preserving slavery.

Joseph Jenkins Roberts, a man born free in Virginia, became the colony’s first Black governor in 1841, and declared Liberia’s independence in 1847; it became the first African colony to gain independence. By then, the American Colonization Society had lost a lot of money and was falling apart. In its Declaration of Independence, Liberia accused the U.S. of injustices that made separation necessary, and urged other countries to recognize its statehood.

Still, the United States did not recognize Liberia as an independent nation until 1862, during the American Civil War. That year, enslaved people in Washington, D.C. won their freedom, and Congress approved funds to relocate those who wanted to move to Liberia or Central America. President Abraham Lincoln still believed at this late date that voluntary colonization should go hand-in-hand with emancipation because he thought Black and white people couldn’t live equally in the same country. Later in the war, however, Lincoln abandoned the idea of colonization and publicly supported Black men gaining the right to vote.

As we said before, blacks constituted a very small portion of the black people in America in the 1800s. We refer to only five percent (5%) of the people while 95% went to the Caribbean, Central America, or South America.

(We might also point out that this was only a small number compared to the many in the world in which slavery was prominent—such as Africa itself, the Middle East, and other places. Slavery was a way of life for many millions in the world and this continued from pre-Christian times, the Middle Ages, on to the modern era.) This in no way justifies a sinful, wrong, and terrible institution—based on greed, hatred, and lack of love. Let’s too remember that “kidnapping” was a prominent sin mentioned in Scripture (1 Timothy 1:10).

But if we view the whole situation, we must say that the “black lives matter” movement does not really understand the situation well. As we pointed out in the article on the website of the past, God values each of us. Thus “all” lives matter to Him—and not just “black” lives.

The information above also points out that many provisions were made for those blacks who were willing to go back to where they came from—Africa. We are not in any way justifying the slaveholders who made this whole enterprise work. Neither do we justify the 95% of those in Brazil, Cuba, the whole Caribbean area, and so forth, that also made the slave trade feasible. This was wrong then and it is wrong today. But we must say that if “Black Lives Matter” people who cause stealing, mayhem, murder, bloodshed, and all sorts of wickedness want to continue their rampage, let them do so then face incarceration—and let them remember what their forbears wanted years ago.

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/slavery

https://www.history.com/news/slavery-american-colonization-society-liberia

http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org › emancipation › text4

You can reach us via e-mail

at the following address:

You can reach us via e-mail

at the following address: