Richard Hollerman

We know that this article and a title like this may cause you to wonder. In fact, if you have strong feelings about this subject, it may not be helpful at all for you to read this. On the other hand, we do hope that you can read with understanding as well as evaluate it all according to God’s Word.

My Early Leaning against the Military

and Present-day Opposition to Warfare!

We know that there are strong feelings on this subject. Refer not only to the 5% of Americans but the 95% of other people in the world. Some of you may have stronger feelings than others. We are followers of Jesus and this will be reflected in the presentation below. Please keep this in mind. Also, we are not unmindful of the various views that exist regarding this subject. May God bless you. Again, we hope that you will read with an open mind. There are many other articles on the website that address this matter and we hope that you will consult them.

I just checked and when I was about age 14 a new movie came out entitled “Friendly Persuasion.” Our family very rarely saw a movie. It was something of a yearly event or sometimes an event every two years or so. But (as I just checked this on the internet) one did come out when I was about age 14. I may have seen it when I was either fourteen or fifteen. As you may know, I turned to Christ and left the Lutheran Church (the denomination in which I was raised as a child) when I was age 15 or 16. Anyway, I am sorry that I make reference to this movie to you because, hopefully, you don’t go to Hollywood movies.

Can God use a wrongful and worldly Hollywood movie to influence one for His own purpose? Can He turn a young person (I suppose that I was about age 14 or 15) from a religious but worldly perspective and lifestyle to one pleasing to Him? In my case, it seemed to work this way. It was more than archaic language and horses and buggies, to a view of life and a non-military perspective.

The film portrayed a Quaker family about 1861 in the Midwest, as I recall. The father was not very sincere, as I remember, but he went along with the religion of his wife and upbringing. (Hopefully, you are aware that the religion of Quakerism is false.) On the other hand, the mother was a sincere Quaker woman. Of course, they used a horse and buggy and dressed in black. I think that they had a son also—whose name I can’t recall. It was the time of the beginning of the Civil War and the son wanted to leave the non-resistant stance of the family (being Quakers or members of the Society of Friends) and enter the army as an active participant.

To make a long story short, there was an Army Officer who wanted to romance the daughter of this Quaker family and eventually did. The familiar music in the background was sung by Pat Boone and it was called “Friendly Persuasion”—the title of the movie. Sadly, the movie had hypocrisy and false teaching in it, and I am not at all encouraging you to go to movies. I doubt that I ever went to a movie again after about age 20, but this is just the background of my comments.

I was somewhat impressed with some parts of this Hollywood movie. As an impressionable 14- or 15-year-old boy, I came to have some convictions about living not as a Quaker but as a person who would object to warfare. It is all a “mix-up” at this point, but I just share what I recall.

When I was about age 16 and was immersed, I learned of a publishing company called Gospel Advocate, and I consumed their catalog! In the catalog I learned of a book entitled Civil Government by David Lipscomb, the writer and a former principle at a “Christian College.” In this volume, Lipscomb showed that the early Christians totally objected to the military. In fact, they didn’t enter warfare until about AD 190 or so and didn’t fully enter it until the time of Constantine, about AD 313 to 325. This was impressive to me. I was developing convictions about war about this time myself. For those who wish to examine more of this author’s views, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_ Lipscomb# Views_on_war_and_government.

I also obtained from the catalog another book entitled The New Testament Teaching on War by H. Leo Boles (AD 1874 to 1946). This was a short but helpful book that fully convinced me of the fact that the early Christians abstained from warfare. It gave a number of reasons why the early Christians saw this as wrong. Interestingly, in the Civil War in America (AD 1861 to 1862), certain ones were able to keep from that war by the order of the government. (Since that time, the book was reissued with three parts, including one by Boles. God and Government, Lee M. Rogers.)

During this time of searching and study, I can also remember going to the local library in the little community where I resided and did some reading into history. I can recall sitting alone in the library room at the shelves and examining the historical section. It was there that I learned that the early believers in Christ refused to enter any carnal conflict at all—at least for some years. In fact, one of the books that I read referred to the military involvement as “carnal warfare” which tells us something about how people often looked on this some time ago (cf. 2 Corinthians 10:4). Thus, various influences led me to take a stand against involvement in warfare and the military.

There were various influences that touched me deeply. One was a simple account of Dirk Williams and his stand. We read this: “Dirk Willems was a Dutch martyred Anabaptist who is most famous for escaping from prison but then turning back to rescue his pursuer—who had fallen through thin ice while chasing Willems—to then be recaptured, tortured and killed for his faith.” (Wikipedia). Why couldn’t I and others see this?

I remember that Dad had told me that a few others also objected to warfare. They were popular figures that people might recognize. There was the famous Hollywood actor named Lew Ayres. Although my father didn’t object to warfare, per se, he cited this actor as one who held to this conviction. Although he technically wasn’t an objector to war in general, Ayres did insist on entering the Second World War and served as a non-combatant. He cared for numerous sick and maimed soldiers and made a name for himself. (This is not a position that I would have taken, but it was his effort to denounce the killing involved.) (See also www.history.net.)

Perhaps we should mention another person who receive a presidential award after the second world war. I refer to Desmond Thomas.

Another movie was made on his life and stance.

I remember also that during the Civil War (also called “The War between the States”), the bloodiest war in U.S. history, there was some allowance for objectors. Abraham Lincoln seemed to be sympathetic to this stand but I don’t remember exactly his view. Shockingly, the official estimate of deaths would be about 620,000, with specific numbers being about 618,222. This would be some 360,222 Union deaths and 258,000 Confederate deaths. This number has recently been estimated to be about 750,000 (with a range of 650,000 to as many as 850,000 deaths). (https://www.history.com/news/american-civil-war-deaths#:~:text=But%20how%20many%20died%20has,deaths%20and%20258%2C000%20Confederate%20deaths.). But we really don’t know. I know and everyone else in the country knows that vast numbers of people were killed—and this was a time when the population was much lower than now!

I don’t know about the Spanish-American War, but in the First World War, especially if one couldn’t defend his stance, there was a 5-year prison sentence. The government did not take kindly to the non-resistant view, thus there was a great amount of opposition to it. Further, we know that this was a “popular war”—the “war to end all wars.” Sadly, this certainly was not the case!

In the Second World War, obtaining this classification was difficult but it could be done. Generally, objectors were sent to national parks and other places where they built bridges and roads. These were set up by the so-called “Historic Peace Churches” (e.g., the Society of Friends [the Quakers], the Mennonites, the Church of the Brethren, the Church of the Brethren, the Amish, and perhaps other like-minded denominations). Surely the Witnesses suffered terribly since they totally objected to involvement.

By the time of the Vietnam War of the 1960s and 1970s (it was over by 1975), the government sent objectors to places such as hospitals and similar organizations where they did menial type of work “for the good of society,” with low pay, and this would enable men to do public service “in lieu of induction” into the military. I think that since that time there has been no draft at all since the government must think that they have enough enlisted men (and women) to do the job. I might add here that through these centuries, women didn’t need to enlist since this was before “women’s liberation” or “feminism” was permitted. Since that time, the door has swung open and women, sodomites, and others are allowed to enlist and serve. Apparently all sorts of people may find a safe haven in the military.

Of course, there were other books and influences in my life. I recall reading one entitled Must the Young Die Too by Wyatt Sawyer (from Fort Worth, Texas). It was a biography of an objector that was another element in this matter. I also remember seeing a movie about this time entitled “All is Quiet on the Western Front” starring Gary Cooper. It was about a First World War objector from Tennessee who changed his views and became a participant, killing many Germans—and being praised and receiving an award from the sitting President. Instead of praising him, of course, we should have lamented his changed stance. So is the “Christian” view of things.

Although I was not influenced by this, still it was another item that was in the public eye. As I recall, I received no commendation or positive statements at school or church, but the books mentioned above did affect me greatly. I could see that the public was going one way, along with religious people, but God’s Word was going a different way. This is the way that I wanted!

I can also recall that my father and none of my uncles on either side were in the war effort. They may not have objected but simply didn’t participate. (Eventually, an uncle did go to the Korean War in the early 1950s and perhaps an ancestor was involved in the Civil War.) Perhaps this too influenced me in some way. My brother and another uncle did enter as soldiers but the other ones didn’t.

Objectors through History

Some of our readers may want to know about the frequency of this stance through the years. We find the following explanation:

During World War II, there were 34.5 million men who registered for the draft. Of those, 72,354 applied for conscientious objector status. Of those conscientious objectors, 25,000 served in noncombatant roles, and there were 12,000 men who chose to perform alternative service

http://archive.pov.org/soldiersofconscience

From this explanation, we see that although (in America) there were numerous men and women who fought (about 34.5 million, which was a huge number), much fewer did apply for the Objector status for the Second World War. According to the records above, we find over 72 thousand who did object and of this number, 25,000 entered the military, but served in a role that didn’t require killing. However, about 12,000 did involve themselves in “alternative service” which would have been supervised by the “historic peace churches” such as the Mennonites and Quakers.

Let’s now cover a survey of objection through the years in America. Much of this information comes from such places as

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscientious_objector.

See also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscientious_objection_in_the_United_States, and others.

See also: https://www.icrc.org/en/archives

In the early years of America, we find that objection to war was freely permitted:

In the colonial age of America, the right to religious freedom was often expressed as the right of an individual to his or her own conscience. This freedom, which was recognized in many of the colonies — and eventually by the first amendment to the Constitution — shielded many religious sects, including pacifist groups such as the Quakers.

Near the beginning of the American Revolution, George Washington called for a draft to fill the ranks of the Continental Army, exempting “those with conscientious scruples against war.”

Some decades later, by the time of the Civil War (also called “The War Between the States”), we do find a reaction to this more liberal stance. As you may recall, the Northern States were pitted against the Southern States. Probably authorities thought that if they would grant exemption, there would be a wholesale objection to war in general. Keep in mind that in both north and south (and especially the South), there were many “religious” soldiers who fought. (This doesn’t mean that they were all “Christians” by any means but only that there was a “religious” presence.)

We find that during the Civil War, the first federally mandated draft in the United States was implemented, and instances of cruel punishment and deaths of conscientious objectors were first recorded, including being starved and hung by their thumbs.

Maybe some of you would respond that this doesn’t sound at all like the United States, but things were different two centuries ago! The First World War (in America) was somewhat of a “popular war” inasmuch as many naïve Americans thought that this was “a war to end all wars.” But millions did participate and many men were killed by the enemy. It was the time of “trench warfare.”

Further, this would have been the time of airplanes, machine guns, and other new weapons. On the battlefront, the Christian, of course, finds all of this abhorrent but we are merely recording what the conditions were. We find this survey:

World War I saw the reinstitution of the draft at the same time that popular opinion was divided over American participation in the war. Government prosecution of conscientious objectors was intense, and resisting conscription or encouraging others to resist conscription led to arrest and imprisonment for many Americans. Of the 450 conscientious objectors found guilty at military hearings during World War I, 17 were sentenced to death, 142 received life sentences and 73 received 20-year prison terms. Only 15 were sentenced to three years or less.

Thus we see that some were put to death because of their stance, some were thrown into prison, and certain others were put in prison for shorter sentences. It was a time of intense persecution as Americans fought against the “enemy” from Germany.

The treatment of these men might be described in this way:

Many conscientious objectors have been executed, imprisoned, or otherwise penalized when their beliefs led to actions conflicting with their society’s legal system or government. The legal definition and status of conscientious objection has varied over the years and from nation to nation. Religious beliefs were a starting point in many nations for legally granting conscientious objector status. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscientious_objector)

By the time of the Second World War (which began in the United States in 1941), we do fine somewhat of better conditions for those who objected to warfare. This is the summary:

In the time leading up to World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt implemented the Selective Service and Training Act of 1940, which was the first peacetime draft in United States history. This period was also marked by the government’s recognition that some would oppose military service for religious or conscientious reasons. During World War II, there were 34.5 million men who registered for the draft. Of those, 72,354 applied for conscientious objector status. Of those conscientious objectors, 25,000 served in noncombatant roles, and there were 12,000 men who chose to perform alternative service.

Those who chose alternative service worked in Civilian Public Service camps. These service camps were operated by religious groups, including churches rooted in the pacifist tradition, such as the Mennonites and the Quakers. These camps predominantly put men to work on improving soil conservation or preserving state and national parks.

Thus we can see that the draft became effective at this time, through presidential proclamation. We think that it could be that America was concerned about the opponents (such as Germany, Austria, Italy, Japan, and others). Again, this was a somewhat “popular” war with millions participating in America! Again, this is the survey:

We read: “34.5 million men who registered for the draft. Of those, 72,354 applied for conscientious objector status. Of those conscientious objectors, 25,000 served in noncombatant roles, and there were 12,000 men who chose to perform alternative service.”

We see that 34.5 million men and women (from America alone) participated (we can only guess how many were involved around the world!). Of this many, over 72,000 objected, 25,000 worked in “noncombatant roles” and there were 12,000 men in “alternative service” that was supervised by such religious groups as the Mennonites, the Society of Friends, and like-minded groups. The Witnesses and ones like them also objected but they had no official means of work. Further, they were thrown into prison for their stance. (This is not to endorse the stance of this heretical group in any way.)

What about the Vietnam War? This, of course, happened in the 1960s and 1970s. Whereas the previous war was a “popular” war (many people chose to endorse it) we must say that this present war was not popular in general. This is what we read:

The Vietnam War, which became a flashpoint for controversy in the 1960s and 1970s, provoked many more individuals to claim conscientious objector status. Over the duration of the conflict, the Selective Service recognized 171,000 conscientious objectors; 3,275 soldiers received discharges for conscientious objector status that developed after their induction into the military. In addition, hundreds of thousands of men, many of whom were conscientious objectors, avoided the draft by leaving the country or refusing to register.

Our view is that many of the above objectors really were not opposed to the war because of what Jesus said or what the early Christians did, but because they objected to this particular war! From the above information, we see that 171,000 received the “objector” status and many thousands fled the country—often to Canada.

We now come to wars that bring us to the present time. We refer to the Gulf War, the War in Afghanistan, and the War in Iraq.

After the end of the draft in 1973, the military became an all-volunteer force. Before the 1991 Gulf War, 2,500 men and women refused to serve based on conscience. Eventually, 111 members of the Army were officially recognized as conscientious objectors.

During the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, far fewer soldiers have made it through the process to become conscientious objectors. In 2006, the Army reported only 42 applications, of which 33 were approved. Advocates and outside observers have argued that these numbers are artificially low because they reflect only those soldiers who complete the lengthy application process. According to the Center on Conscience and War, they received one to two calls per month to their GI Rights Hotline in 2000 and 2001 from someone in the military raising questions of conscience. By 2002 and 2003, they were receiving at least one to two such calls per day.

The conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq have been the occasion for a growing number of desertions — defined by the military as soldiers absent without leave for more than 30 days. In 2006, the Army reported 3,196 desertions, a sharp increase from two years earlier, which saw 2,357 desertions. At the same time, the number of prosecutions for desertion went up, a move described by military lawyers as an effort to discourage soldiers from leaving their assignments.

Currently, to qualify for conscientious objector status a member of the military must demonstrate that he or she has a “firm, fixed and sincere objection to participation in war in any form or the bearing of arms, by reason of religious training and belief.” Objections based on a particular conflict or on political considerations are not considered. All incoming soldiers must sign a statement that they are not conscientious objectors. Therefore, any conscientious objector applicant must also demonstrate that this belief “crystallized” — or solidified — during their military service.

Soldiers who want to claim conscientious objector status may face a difficult burden of proof. Applicants are interviewed and evaluated by a chaplain, a psychiatrist and an investigating officer. Their applications must be submitted in writing to a review board, but soldiers are not permitted to appear in person before the board. Applications that are rejected are not eligible for reconsideration.

We learn from this that few people do seek to gain the Objector status today and those who do may or may not be accepted. In other words, the Christian stance is unlikely to pass and be available to interested readers. We must remember also that the draft was no longer being practiced.

The following would be some of the addresses associated with our presentation and the information we’ve given above:

Civil War

» Lillian Schlissel, Conscience in America: A Documentary History of Conscientious Objection in America, 1757-1967 (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1968).

World War I

» Stephen Kohn, Jailed for Peace: The History of American Draft Law Violators, 1658-1985 (Westport, CT: Praeger Paperback, 1987).

World War II

» “Civilian Public Service Camps,” Ohio History Central (July 1, 2005).

» “Nebraskans on the Front Lines,” Nebraska Studies.

» “Conscientious Objection and Alternative Service,” Selective Service System.

Vietnam War

» L. Baskir and W. Strauss, Chance and Circumstance: The Draft, the War and the Vietnam Generation (New York: Knopf Press, 1978).

» Margaret Levi, Consent, Dissent, and Patriotism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Gulf War & Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan

» “Army Is Cracking Down on Deserters,” The New York Times (April 9, 2007).

» “Fighting Not To Fight,” The Guardian (April 1, 2003).

» The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It, Independent Television Service.

» “A Nation at War: Dissent — Conscientious Objector Numbers Are Small But Growing,” The New York Times (April 1, 2003).

» “Soldiers’ Choice: Fight or Flight,” The Denver Post (April 14, 2007).

Application Procedure

» “Army Is Cracking Down on Deserters,” The New York Times (April 9, 2007).

» “Conscientious Objection and Alternative Service,” Selective Service System.

» Gillette v. United States 401 us 437 (1971).

» “Soldiers’ Choice: Fight or Flight,” The Denver Post (April 14, 2007).

We now must ask about what God in His Word says about fighting and killing one’s enemy. At this point, we know what America believes and does and what this country provides, but what does God say about this important subject? Let’s remember that what God says and what man says is often contrary (see Acts 5:19 and 4:19-20).

Scripture

There were some influences in Scripture that led me in a certain direction. I knew of certain passages that could be interpreted in a way that would give credence to a Christian’s involvement in carnal warfare. I refer to such passages as Luke 22:38; Romans 13:1-7; Acts 25:11 and others. These would lead in a certain direction and I often heard them quoted. In fact, people do use them frequently to support their position.

Years ago, I also was influenced by certain places in Scripture that show us that Jesus taught against warfare—or against aggression, killing, fighting, and hostility. These Scriptures and ones like them forbad the apostles and others from engaging in warfare; they also refused to allow our Lord to participate in warfare Himself. See especially such passages as Matthew 5:38-42; 26:52; Romans 12:17-21; 13:1-7; and1 Thessalonians 5:15.

As I studied this, it was also very impressive to me that early Christians refused to fight. They abstained totally from all of this carnal involvement in their lives. The early believers didn’t participate for some 174 after the time of Christ. Finally, about the time of Constantine (the Roman governor), some few did participate in warfare about AD 313 (the Edict of Toleration) to 325 (Nicaea).

I also found it interesting in reading the books mentioned earlier as well as many historical books since, that early “Christian” writers taught against Christians participating in warfare and bloodshed. I refer to such writers as Justin Martyr, Tertullian, Irenaeus, and others. Then, after about AD 174, they didn’t totally forbid this involvement but continued to teach against this for many decades until the time of Constantine (AD 313 to 325). You might also remember that the “falling away” occurred in the second century.

For those interested, let’s quote a small portion of a book by William Paul entitled A Christian View of Armed Warfare:

A.D.C.J. Cadoux, acknowledged as the best authority on the subject, said, “No Christian ever thought of enlisting in the army after his conversion until the reign of Marcus Aurelius (AD 161 to 180) at earliest. Hershberger verifies this statement by saying, “It is quite clear that prior to about AD 174 it is impossible to speak of Christian soldiers.” Still another voice may be added to testify that Christian participation in war was unheard of in the early church. Bainton tells us, “From the end of the New Testament period to the decade AD 170-180 there is no evidence whatever of Christians in the army.

I am not sure but probably others also opposed the Christian participation in war. I refer to such writers as Hippolytus, Clement of Alexandria, Papias, Clement of Rome, Tatian, and others. I found this to be quite impressive.

(See also the book above by Paul. We offer the personalities that he quotes in his book, pages 47-61. Justin Martyr, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Origin, Lactantius, Arnobius.)

As to objectors in history, consider this.

Currently, to qualify for conscientious objector status, a member of the military must demonstrate that he or she has a “firm, fixed and sincere objection to participation in war in any form or the bearing of arms, by reason of religious training and belief.” Objections based on a particular conflict or on political considerations are not considered. All incoming soldiers must sign a statement that they are not conscientious objectors. Therefore, any conscientious objector applicant must also demonstrate that this belief “crystallized” — or solidified — during their military service.

After induction, we find this:

Soldiers who want to claim conscientious objector status may face a difficult burden of proof. Applicants are interviewed and evaluated by a chaplain, a psychiatrist and an investigating officer. Their applications must be submitted in writing to a review board, but soldiers are not permitted to appear in person before the board. Applications that are rejected are not eligible for reconsideration.

(https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/912/conscientious-objection-to-military-service)

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscientious_objector).

We know that this is a relatively long excerpt but it does seem related to the topic:

What is a Conscientious Objector? One who is conscientious objector, one who opposes bearing arms or who objects to any type of military training and service. Some conscientious objectors refuse to submit to any of the procedures of compulsory conscription. Although all objectors take their position on the basis of conscience, they may have varying religious, philosophical, or political reasons for their beliefs.

Conscientious objection to military service has existed in some form since the beginning of the Christian era and has, for the most part, been associated with religious scruples against military activities. It developed as a doctrine of the Mennonites in various parts of Europe in the 16th century, of the Society of Friends (Quakers) in England in the 17th century, and of the Church of the Brethren and of the Dukhobors in Russia in the 18th century.

Throughout history, governments have been generally unsympathetic toward individual conscientious objectors; their refusal to undertake military service has been treated like any other breach of law. There have, however, been times when certain pacifistic religious sects have been exempted. During the 19th century, Prussia exempted the Mennonites from military service in return for a military tax, and until 1874 they were exempted in Russia. Such exceptions were unusual, however.

The relatively liberal policy of the United States began in colonial Pennsylvania, whose government was controlled until 1756 by Quaker pacifists. Since the American Civil War and the enactment of the first U.S. conscript law, some form of alternative service has been granted to those unwilling to bear arms. Under the conscript laws of 1940, conscientious objector status, including some form of service unrelated to and not controlled by the military, was granted, but solely on the basis of membership in a recognized pacifistic religious sect. Objections of a philosophical, political, or personal moral nature were not considered valid reasons for refusing military service.

In Great Britain a noncombatant corps was established during World War I, but many conscientious objectors refused to belong to it. During World War II, three types of exemption could be granted: (1) unconditional; (2) conditional on the undertaking of specified civil work; (3) exemption only from combatant duties. Conscription in Great Britain ended in 1960, and in 1968 recruits were allowed discharge as conscientious objectors within six months from the date of their entry into the military.

Until the 1960s neither France nor Belgium had legal provision for conscientious objectors, although for some years in both countries growing public opinion—fortified in France by the unpopularity of the Algerian War of Independence—had forced limited recognition administratively. A French law of 1963 finally gave legal recognition to religious and philosophical objectors, providing both noncombatant and alternative civilian service with a term of service twice that of the military term. Belgium enacted a similar law in 1964, recognizing objection to all military service on religious, philosophical, and moral grounds.

Scandinavian countries recognize all types of objectors and provide both noncombatant and civilian service. In Norway and Sweden civil defense is compulsory, with no legal recognition of objection to that type of service. A Swedish law of 1966 provided complete exemption from compulsory service for Jehovah’s Witnesses. In the Netherlands, religious and moral objectors are recognized. During the period of German partition (1949–90), the Federal Republic (West Germany) recognized all types of objectors, providing noncombatant service and alternative civilian service, while after 1964 East Germany provided noncombatant military services for conscientious objectors.

(The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. This article was most recently revised and updated by Brian Duignan.)

We know that this article excerpt, although thorough, is limited for it majors on Europe and not on the remainder of the world—unfortunately.) We also wonder why we don’t read of objectors in other parts of the world. Are there none?

We not come to another excerpt that is worth reading:

Many conscientious objectors have been executed, imprisoned, or otherwise penalized when their beliefs led to actions conflicting with their society’s legal system or government. The legal definition and status of conscientious objection has varied over the years and from nation to nation. Religious beliefs were a starting point in many nations for legally granting conscientious objector status.

The first recorded conscientious objector, Maximilianus, [who was] conscripted into the Roman Army in the year 295, but “told the Proconsul in Numidia that because of his religious convictions he could not serve in the military”. He was executed for this, and was later canonized as Saint Maximilian. (Ibid.)

We continue to read of the early years (in the previous centuries) in this way:

Formal legislation to exempt objectors from fighting was first granted in mid-18th-century Great Britain following problems with attempting to force Quakers into military service. In 1757, when the first attempt was made to establish a British Militia as a professional national military reserve, a clause in the Militia Ballot Act allowed Quakers exemption from military service.

In the United States, conscientious objection was permitted from the country’s founding, although regulation was left to individual states prior to the introduction of conscription. (Ibid.)

We do know, of course, that this religious denomination was not at all the only one who was committed to non-resistance, but various ones also objected in Great Britain, the United States, and other nations. Further, this was not merely a denominational matter, but it extended to individuals as well.

(The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, This article was most recently revised and updated by Brian Duignan.)

This refusal to participate in war was categorized as a “human right” but this had mixed blessings and was not entirely correct. Various groups in the United States may voice their objection to any war. We find that

Holiness Pacifists such as the Reformed Free Methodist Church, Emmanuel Association of Churches, the Immanuel Missionary Church, and the Church of God (Guthrie, Oklahoma) would so object, for they object to war from the conviction that Christian life is incompatible with military action, because Jesus enjoins his followers to love their enemies and to refuse violence. (Ibid)

Of course, we would add that thousands of congregations and individuals identified as “Churches of Christ” would also object. (This was particularly true in the 19th century but it continues to some extent today.)

Further explanation may be found by reading this:

The Book of Discipline of the Reformed Free Methodist Church teaches:

Militarism is contrary to the spirit of the New Testament and the teachings of Jesus Christ. Even from humanitarian principles alone, it is utterly indefensible. It is our profound and God-given conviction that none of our people be required to participate in war of any form and that these God-given convictions of our members be respected.

We realize that we, as Christians, are opposed to all denominationalism and Disciplines, but this excerpt does show that different denominations do renounce war in all of its forms. We note that various groups that are generally known as “cults” may also object:

Since the American Civil War, Seventh-day Adventists have been known as non-combatants, and have done work in hospitals or to give medical care rather than combat roles, and the church has upheld the non-combative position.

Jehovah’s Witnesses and Christadelphians, also refuse to participate in the armed services on the grounds that they believe they should be neutral in worldly conflicts and often cite the latter portion of Isaiah 2:4 which states, “…neither shall they learn war anymore.” Other objections can stem from a deep sense of responsibility toward humanity as a whole, or from simple denial that any government possesses the moral authority to command warlike behavior from its citizens.

As we continue to examine the early Christian teaching and latter teachings regarding warfare, we find a further description. For example:

In the early Christian Church followers of Christ refused to take up arms.

In as much as they [Jesus’ teachings] ruled out as illicit all use of violence and injury against others, clearly implied [was] the illegitimacy of participation in war … The early Christians took Jesus at his word, and understood his inculcations of gentleness and non-resistance in their literal sense. They closely identified their religion with peace; they strongly condemned war for the bloodshed which it involved.

C John Cadoux (1919). The Early Christian Attitude toward War.

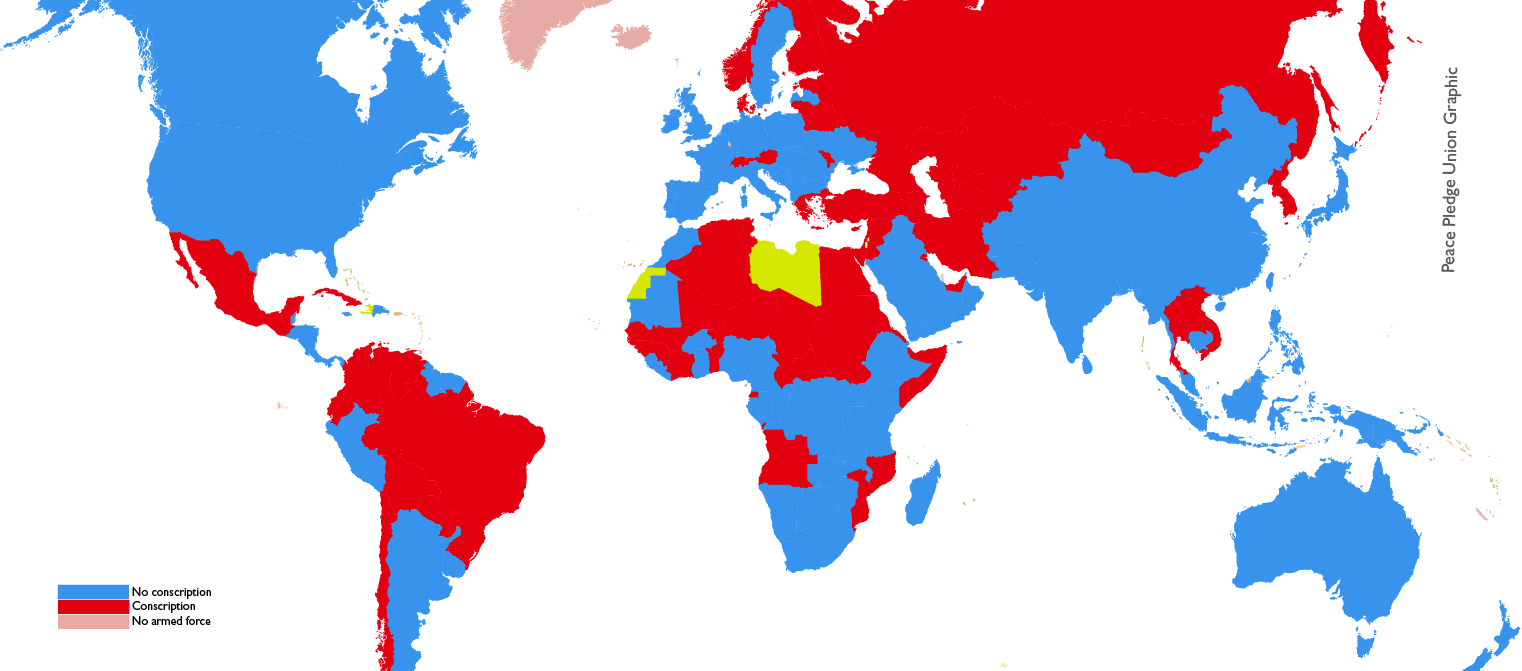

As we come to the end of our survey, we note that objection to warfare is not found in many countries but is found in some other countries. This highlights what we may find:

Conservative Mennonites do not object to serving their country in peaceful alternatives (alternative service) such as hospital work, farming, forestry, road construction and similar occupations. Their objection is in being part in any military capacity whether noncombatant or regular service. During World War II and the Korean, Vietnam war eras they served in many such capacities in alternative I-W service programs initially through the Mennonite Central Committee and now through their own alternatives.

Despite the fact that international institutions such as the United Nations (UN) and the Council of Europe (CoE) regard and promote conscientious objection as a human right, as of 2004, it still does not have a legal basis in most countries. Among the roughly one-hundred countries that have conscription, only thirty countries have some legal provisions, 25 of them in Europe. In Europe, most countries with conscription more or less fulfill international guidelines on conscientious objection legislation (except for Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, Finland and Russia) today. In many countries outside Europe, especially in armed conflict areas (e.g. Democratic Republic of the Congo), conscientious objection is punished severely.

In 1991, The Peace Abbey established the National Registry for Conscientious Objection where people can publicly state their refusal to participate in armed conflict.

From this, we can see that in some countries (such as the Congo) Objection is not permitted at all! We can only guess whether young Christians are either punished with long prison sentences or are put to death. The same would be true of others. As for such places as Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, Finland, Russia, we assume that either Christian objectors are thrown into prison or put to death.

We gather from the above excerpt that many dozens of countries do believe in and practice conscription, but many (most?) of them refuse to allow freedom of conscience and the right to object to violence, hostility, and war. If you live in a nation that allows for this freedom, let us thank God and take heart. May the Lord bless those who object to war and still maintain their convictions.

As we read the excerpt above, we note that generally provision is found in Europe, the United States, and a few other nations. However, in numerous other countries (over 100 of them) we find no provision at all for opposition to warfare. In fact, in many of these nations, people are either forced to enter the military, or are thrown into prison, or even executed!

There is so much written about this subject on Wikipedia and many other sources but we wonder why there is either little or nothing written on the subject from the standpoint of such well-known places as the Islamic countries, India, China, Japan, Africa, South America, and elsewhere. There seems to be many from America and Europe but a dearth of information from other nations. We wonder why this might be.

(By the way, the crushing, debilitating, and wicked way that China has put down descent may be read here: https://www.cfr.org/article/communist-chinas-painful-human-rights-story. This gives us the strong impression that any protest against the present regime and allowance for objections is nearly unheard of.)

Our readership is from many different countries, but prominent among them would be places like the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, the Philippines, Nepal, Nigeria, Hong Kong, Australia, India, South Africa, as well as others. Thus, we find it unusual that places such as China, Russia, Japan, Indonesia, Egypt, Columbia, Mexico, and the like are not included. Either these places do not find this information useful, or the governments have prohibited access to them, or the respective religions fail to encourage such information, or perhaps something else.

We hope that our little discussion on religious objection to warfare will be of interest to you. We know that Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and other such religions would not find this information helpful or relevant. Some would actively oppose it. Thankfully, many thousands of people do find all of this to be helpful, interesting, and useable.

A related but relevant issue would not be “non-resistance” but “pacifism.” We read this:

Pacifism covers a spectrum of views, including the belief that international disputes can and should be peacefully resolved, calls for the abolition of the institutions of the military and war, opposition to any organization of society through governmental force (anarchist or libertarian pacifism), rejection of the use of physical violence to obtain political, economic or social goals, the obliteration of force, and opposition to violence under any circumstance, even defence of self and others. Historians of pacifism Peter Brock and Thomas Paul Socknat define pacifism “in the sense generally accepted in English-speaking areas” as “an unconditional rejection of all forms of warfare”. Philosopher Jenny Teichman defines the main form of pacifism as “anti-warism”, the rejection of all forms of warfare. Teichman’s beliefs have been summarized by Brian Orend as “… A pacifist rejects war and believes there are no moral grounds which can justify resorting to war. War, for the pacifist, is always wrong.” In a sense the philosophy is based on the idea that the ends do not justify the means.

For those interested in this subject, you might consult the following:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pacifism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscientious_objector

You may also find the following worth consulting:

As we have said earlier, we have often wondered about such religions as Islam and how they are able to handle objection to war and violence, inasmuch as Muhammad was a person who killed and maimed, and either killed or hurt others. We think that generally the 2 billion Muslims in the world would choose to fight and not refuse which would be more of a Western view.

There seems to be many places where the governments do not permit this stance. As to those that do (as reflected in the above map) we wonder if this is really accurate. (https://menwhosaidno.org/costoday/costoday.html)

We believe that it may be difficult for a Muslim to object to violence and warfare when they must surely know the many people that Muhammad and his followers murdered and killed over the years. This Muslim view has continued for many centuries (since the seventh century).

Although we have searched on the internet to discover the views of various Eastern countries to warfare, violence, and the like, this is not a common subject. We have also been interested in China and other communist lands. We know that this encompasses hundreds of millions of people (there are 1.4 billion Chinese) and surely there are some professing “Christians” in these countries. What do they do when they would oppose the government and violence or warfare? Would they be thrown into prison, or executed, or passed over, or what? These are questions that could be relevant, especially for Christians and missionaries to these lands. But where is the information?

May God bless you in your own search to know and do God’s will. Let’s remember what Scripture that “the one who does the will of God lives forever” (1 John 2:17). This includes you and me!

Bibliography

You may wish to consult the following books:

What would Jesus Do? John H. Yoder

What Would You Do? John H. Yoder

The Christian Witness to the State, John Howard Yoder

How Christians Made Peace with War, John Driver

A Christian View of Armed Warfare! William Paul

Jesus and Human Conflict, Henry A. Fast

God and Government, Lee M. Rogers

The Christian and Warfare, Jacob J. Enz

Study War No More, ed. David S. Young

Joining the Army that Sheds No Blood, Susan Clemmer Steiner

The New Testament Basis of Pacifism, G.H.C. Macgregor

War: A Trilogy, A. S. Croom

The Way God Fights, Lois Barrett

Be a Man, Son, William Kay Moser

The New Testament Teaching on War, H. Leo Boles

“Address on War,” Alexander Campbell

“Menno Simons,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menno_Simons.

Applied Nonresistance

How to Teach Peace to Children, J. Lorne Peachy

A Time to Kill and a Time to Heal, J. M. Shank

The Principle of Nonresistance, John Horsch

Nonresistance: God’s Plan for the Church

Do Followers of Jesus Fight? Edward Yoder

I Couldn’t Fight.

Report for Duty, Lily A. Bear

The New Testament, the Christian, and the State, Archie Penner

Christianity and Carnal Warfare

The Way of the Cross in Human Relations, Guy Franklin Hershberger

Choosing against War: A Christian View, John D. Roth

What of Noncombatant Service? Melvin Gingerish

Before You Decide

Should Christians Fight? I. C. Wellcome

War and the Gospel, Jean Lasserre

Why We Are Conscientious Objectors to War, William R. McGrath

You can reach us via e-mail

at the following address:

You can reach us via e-mail

at the following address: